What it Was Like to Witness the End of the Oakland A's

It didn't have to be this way

OAKLAND -- On Thursday afternoon under a bright blue Northern California sky I sat amongst 46,899 spectators and witnessed a preventable death.

For nine innings, the indefatigable crowd chanted “Let’s go Oakland!” as both a rallying cry and plea: surely someone, somewhere would step in and stop the madness of the city’s beloved baseball team being ripped away for no good reason by a billionaire villain before time ran out.

Rob Manfred, MLB’s aloof commissioner who once called the World Series trophy “a piece of metal” to downplay its significance, was nowhere to be found: save for a large MANFRAUD banner that A’s fans hung over the right field fence.

John Fisher—the A’s failson nepo baby owner who bought the team with money his parents earned from founding The Gap—also appeared to be in hiding. But it was understood by everyone in the building that his actions were responsible for every tear shed, every hug goodbye, every shrug, and everyone who sat stunned and stared off into the distance when it was all over.

The vibe at the Coliseum on Thursday was funereal.

When the A’s clubhouse opened to media, “American Pie” by Don McLean was blaring from an oversized boombox. Very few players were in the room. A basketball hoop hung from a pillar in the center of the locker room, and an autographed green A’s t-shirt signed by the “Hawk Tuah” girl hung from its rim.

I could not have invented a grimmer scene.

The playlist of sad songs continued until halfway through the Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody” when someone finally had enough and changed it to the greatest hits of the Bay Area’s most famous rapper, Tupac Shakur.

My cell phone reception was terrible, so I connected to the clubhouse WiFi. Would you believe it if I told you that the password to the WiFi in the A’s clubhouse was “P1ayOff$’?

It should be noted here that the A’s announced in 2021 that they would honor their long time clubhouse equipment manager Steve Vucinich by renaming the locker room after him to commemorate his 54 years working for the team. They never did, because this ownership group loves nothing more than breaking its promises.

Players and employees scurried in and out with stadium mementos. Rookie Lawrence Butler had a cardboard cutout of the A’s 2024 schedule next to his locker that his teammates took turns signing. Except I learned that his name isn’t Lawrence, it’s Law. Everyone has called him Law his whole life. Ask for “Lawrence” and you will get a look like you are an out-of-town vulture in town to pick over the team’s carcass (Which, fair enough).

I asked an A’s staffer why, if the team’s young breakout star is being called by the wrong name, he hasn’t corrected anyone. I was told it’s probably because he’s a really polite kid who is just happy to be here. “You gotta remember that every player on this team is like twenty-three years old,” the employee told me.

The fact that every player on the team is either in his early 20’s or barely hanging on to a job in the big leagues or both definitely worked to the A’s benefit on the PR front during this mess. Every player knew what was happening was wrong, but nobody had the seniority or the standing to rip Fisher a new one to the press.

A’s legend Rickey Henderson—who had just told the great Susan Slusser of the San Francisco Chronicle that “I can’t be sad [about the A’s leaving], I have too much money,”—was walking around with his keepsake from the stadium where the field bears his name: a number 4 from the scoreboard. I had assumed he also grabbed the number “2,” since his number was 24, but with Rickey you never know. I later saw a clubbie carrying Rickey’s “4.” It had been signed by the A’s starting lineup that day, in order.

A’s manager Mark Kotsay held his scrum in the dugout and greeted the dozens of media members packed in by saying “welcome to the jungle” with a chuckle. He said he wanted to keep his sunglasses on because he knew he would start crying, but then he took them off because he’s a good sport.

Someone asked what Kotsay was taking from the Coliseum on his way out. He said he had asked for the bases. Realizing this seemed like quite a special haul, he clarified that the bases would be switched out after each inning, and that groundskeeper Clay Wood would receive the bases from the first inning because he deserved them. There would be 27 bases to divvy up at the end of the game.

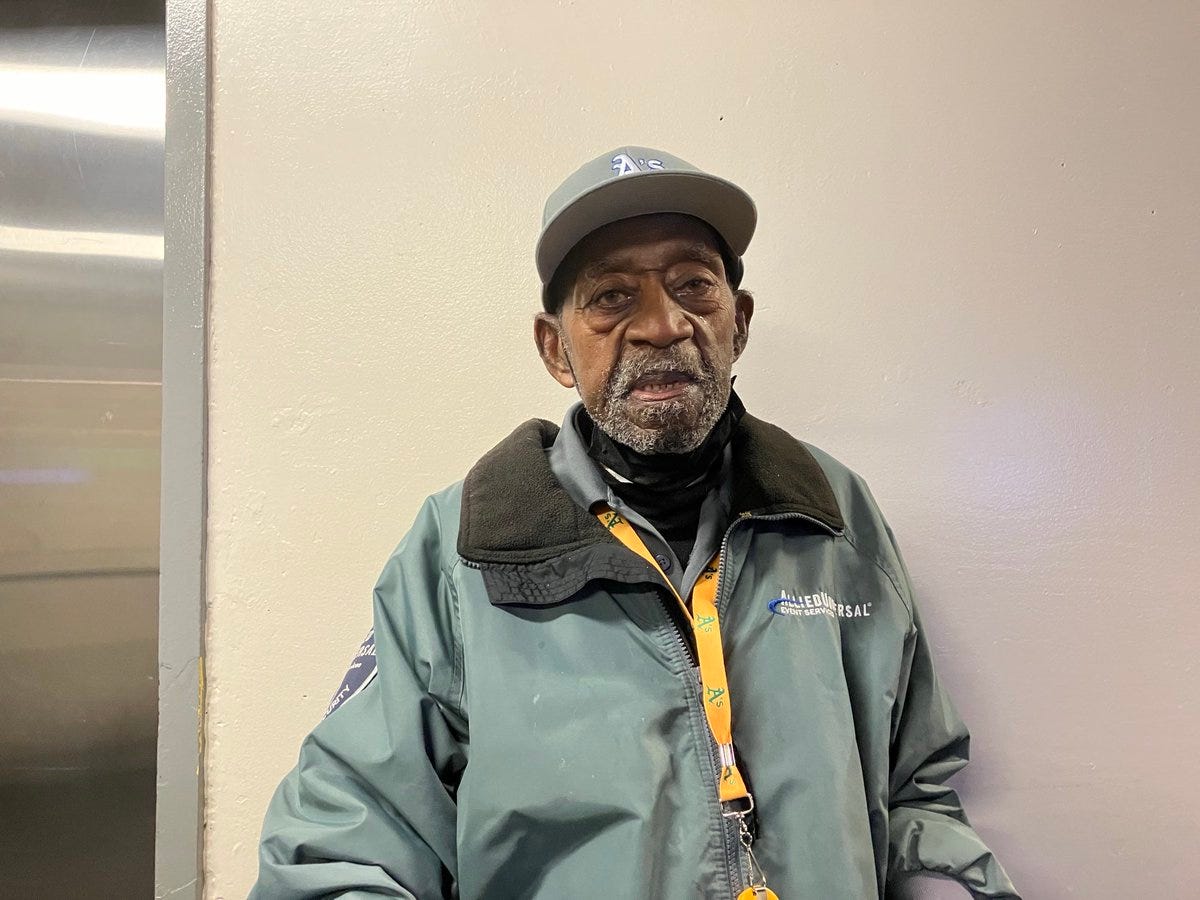

Kotsay held it together until he started talking about the Coliseum workers, and then he began to cry when talking about Gus Dobbins, a 92-year-old doorman who Kotsay had known since he joined the A’s as a player in 2004. Kotsay said he took a photo with Dobbins, and it will go on the desk of “whatever office” he occupies next.

I spoke with a few dozen Coliseum workers and asked them if they were making the move with the team to Sacramento. Most of them were senior citizens who had worked for the team for decades. Most of them said they had not been invited, and did not know if they would be. Many said that even if they were asked to keep working for the team, that the commute was too far, too hard, too much.